Take another seven-week journey to realign with our highest values

By Rabbi Rachel Barenblat / Congregation Beth Israel of the Berkshires

Summer is the season when I feel most out-of-sync with the Jewish calendar. After the spiritual high of receiving Torah anew on Shavuot, this Jewish season takes a deep dive into sorrow.

First comes the 17th of Tammuz (this year, July 13), when we remember a long-ago first breach in Jerusalem’s walls. The 17th of Tammuz is also understood as the anniversary of the date when Moshe broke the first set of tablets in sorrow and fury. Then come the Three Weeks, a period of mourning and remembrance. And then we reach Tisha b’Av (this year, beginning on August 2). Tisha b’Av is the saddest day of the Jewish communal year, when we remember the fall of both Temples and a long list of other catastrophes that have befallen our people.

Jewishly speaking, summer is kind of a downer. And that’s a challenge for me. I’m one of those people who looks forward to summer all year. The moment we reach the solstice in December, I breathe a sigh of relief. At last the days are getting longer! I remind myself that the plants and trees aren’t dead, they’re merely dormant, and soon the world will be green and alive again.

Now that summer is finally here, I want to cherish every moment of daylight. I want to bask in the long light of evening, to feast my eyes on our gorgeous verdant hills, to pick strawberries and snap peas. I want to picnic on the lawn at Tanglewood, rock gently on a porch swing, close my eyes and soak up sun. I don’t want to mourn right now; do you?

It doesn’t help that the Three Weeks and Tisha b’Av are unfamiliar to a lot of liberal American Jews. In my family of origin, “that’s gonna happen right after tishabuv” was a way of saying that something was never going to happen, a kind of kosher variant on “when pigs fly.” If my father (of blessed memory) knew what Tisha b’Av was or when in the year it might fall, he never let on.

As a rabbi, I’ve struggled to figure out how to open up the meaning of this Jewish season to those whom I serve. Most liberal American Jews don’t observe the Three Weeks or Tisha b’Av. And this year in particular, “let’s sit with the world’s brokenness” feels like a tough sell. Amidst climate crisis and global upheaval, who among us needs more reminders of tragedy and grief?

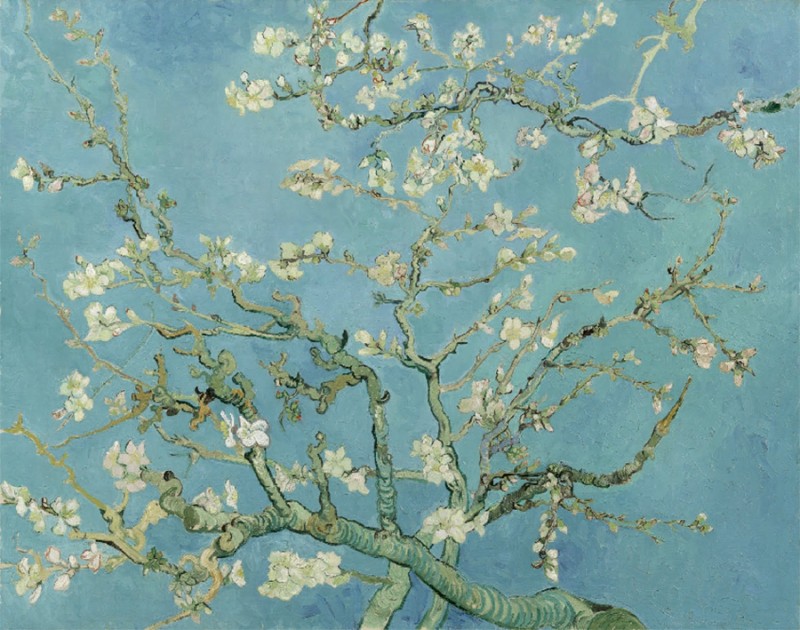

Here’s another way to understand the Three Weeks. This comes from Rabbi Shmuel Eidels, also known as the Maharsha, who lived in Poland around the turn of the 16th century C.E. The Maharsha teaches that this summer period of semi-mourning is a period of growth toward fruition. Just as it takes 21 days for an almond tree to blossom, he says, we can understand the 21 days between the fast of 17 Tammuz and the fast of Tisha b’Av as a period of inner preparation for flowering.

I love this teaching because it completely recasts what this season is for. It’s not (just) for mourning what’s broken; it’s also for nurturing the seeds of something new.

And that, in turn, reminds me that Tisha b’Av isn’t just the low point of our collective spiritual year. It’s also the springboard into what comes next. After Tisha b’Av we reach the “seven weeks of consolation,” marked by haftarah readings that are meant to comfort and uplift.

Following in the footsteps of my teacher Reb Zalman z”l, I understand that corridor of time as the “reverse Omer.” In the spring we count 49 days between Pesach and Shavuot, between liberation and revelation. Many of us have the custom during the Omer of reflecting on inner qualities that our tradition teaches we share with God, such as lovingkindness, strength, and balance. Starting at Tisha b’Av, we can count 49 days to Rosh Hashanah. It’s another seven-week journey of preparing for new beginnings, reflecting on those same human-and-holy qualities. During the reverse Omer we refine our character and realign with our highest values.

I’ve always liked the tradition that teaches that the messiah will be born on Tisha b’Av. Even if we aren’t sure we believe in a messiah, we can understand that as a teaching about finding the spark of hope in life’s darkest times. It’s like the Greek myth about Pandora opening a box of famine and disease and war, and finally unearthing hope, tucked away at the bottom of the box.

If the traditional practices of the Three Weeks and Tisha b’Av don’t speak to us, or if we can’t bear the thought of marinating in more grief this year, I invite us to try thinking like an almond tree that’s slowly getting ready to bloom. (I know that the Maharsha didn’t mean his teaching as an alternative to traditional practices, but I think it can serve that way for those of us who don’t resonate with our tradition’s summer mourning customs.)

Jewishly, we can choose to experience the height of summer as a time of sweetness and self-nurturing, preparation for a future blossoming that maybe we can’t even yet imagine. Amidst American summer rituals like barbecues and beach visits and baseball games, we can make space for spiritual curiosity about who we’re becoming and what inner qualities we want to uplift.

The Three Weeks and Tisha b’Av are reminders of what’s broken in our history and in our hearts. The question I’m bringing to this season is: what seeds might be planted in life’s broken places, that over this season could be silently preparing themselves (preparing us) to flower into something new?

Rabbi Rachel Barenblat is the spiritual leader of Congregation Beth Israel of the Berkshires in North Adams. She blogs as The Velveteen Rabbi at velveteenrabbi.blogs.com.

Image: Almond Blossom (1890) by Vincent van Gogh from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam